| |

Following research into Old Palmerians who died in the

two World Wars I (Neil Beaumont) discovered that an Old Palmerian, Gordon

Charles Steele, won the Victoria Cross after taking part in a motor torpedo

boat raid on Kronstadt Harbour on the 18th August 1919.

The information below derives from information from a wide range of primary

and secondary sources and a fuller account is intended to be published.

The Victoria Cross is renowned throughout the world and is awarded only

for “most conspicuous bravery, or some daring pre-eminent act of

valour or selfsacrifice or extreme devotion to duty in the presence of

the enemy”.

Only 1355 Victoria Crosses have been awarded and the first presentation

was made by Queen Victoria on 26th June 1857.

It is now 93 years since Gordon Steele won the Victoria Cross, the highest

honour this country can bestow for bravery, and, at last, I am proud to

say that he will be remembered by a memorial in the College Library.

A plaque, presented by the Association, designed and crafted by John Sach

and made from Indian Silver Wood from the old Boys’ School Library,

is intended to be [has been] unveiled in 2012.

The Supplement to the London Gazette of Tuesday, 11th November1919 published

the following citation in respect of the award of his Victoria Cross:-

“Lieutenant Gordon Charles STEELE. Royal Navy.

For most conspicuous gallantry, skill and devotion to duty on the occasion

of the attack on Kronstadt Harbour on the 18th August 1919.

Lieutenant Steele was second-in-command of H.M. Coastal Boat No. 88.

After this boat had entered the harbour the Commanding Officer, Lieutenant

Dayrell- Reed, was shot through the head and the boat thrown off her course.

Lieutenant Steele took the wheel , steadied the boat, lifted Lieutenant

Dayrell- Reed away from the steering and firing position and torpedoed

the Bolshevik Battleship “Andrei Pervozvanni” at a hundred

yards range.

He had then a difficult manoeuvre to perform to get a clear view of the

Battleship “Petropavlovsk” which was overlapped by the “Pervozvanni”

and obscured by smoke coming from that ship. The evolution, however, was

skilfully carried out and the “Petropavlovsk” torpedoed. This

left Lieutenant Steele with only just room to turn, in order to regain

the entrance to the harbour, but he effected the movement with success

and firing his machine guns along the wall on his way, passed under the

line of forts through a heavy fire out of the harbour.”

GORDON CHARLES STEELE,V.C., R.N.

The first entry I found was in the 1934/5 School Yearbook which included

“Commander G.C.Steele,V.C., R.N., Captain Superintendent of H.M.S.

Worcester”.

School records showed Gordon Charles Steele entered Palmer’s in

the Michaelmas Term of 1905 along with two of his brothers, William Jermyn

and Arthur Daveney Steele. Previously, they had attended Vale College

in Ramsgate, Kent. Another brother, John D’Arcy Steele, entered

the School in 1911, he had been previously educated at home.

Gordon was born in Exeter on 1st November 1891 and his parents were Henry

William Steele and Selina May Steele, née Symonds. The naval tradition

was strong in the family as Gordon’s father was serving in the Royal

Navy and his maternal grandfather served as a General in the Royal Marine

Light Infantry.

Henry Steele entered service in the Royal Navy in 1869 and enjoyed a distinguished

naval career including being mentioned in despatches. He retired with

the rank of Captain and was appointed Captain Superintendent of the Training

Ship “Cornwall”, moored at Purfleet, and the Steele family

moved to the area.

During Henry Steele’s time in charge of the “Cornwall”,

he made many improvements in respect of the boys’ welfare and the

Ship’s facilities.

“Cornwall” boys were provided with a good elementary educational

grounding together with naval training and Captain Steele also instituted

a system which offered supervision of the boys when they left the Ship

to try to ensure they made good progress.

Captain Steele was 60 years old when he died in January 1916. He left

a widow, four sons and three daughters and the funeral took place at Aveley

Parish Church.

On leaving Palmer’s at the end of the Lent Term in 1907, Gordon

Steele joined the training ship H.M.S. “Worcester”, moored

off Greenhithe across the Thames from the “Cornwall”. The

“Worcester” trained boys to serve as officers in the merchant

navy and, on leaving, Gordon joined the Peninsular and Oriental Line and

also chose to enrol in the Royal Naval Reserve as a Midshipman.

After induction training at the outbreak of the First World War, Gordon

undertook specialist submarine training and was one of the elite recruited

into submarine warfare which was in its infancy.

By the end of 1914 Gordon was aboard the S.S. “Vienna”, a

purpose–built railway passenger ship moored at Harwich, and used

as an overflow depot ship for submarine officers. Before the War it transported

passengers to and from the Hook of Holland. Shortly, she was to be fitted

out as an armed decoy steamer and become one of a secret force known as

“Q-Ships”.

During its adaptation the “Vienna”, alias the “Antwerp”,

was provided with two 12-pounder guns hidden beneath a decoy frame in

which holes were cut to enable expert Marine rifle marksmen to fire through.

By the end of January 1915 the “Vienna” was ready for war

service in its new role. Sub–Lieutenant Steele was appointed second–in-command

and Gunnery Officer, serving under Lt.-Commander Geoffrey Herbert who

was an expert in submarine warfare.

As a decoy ship, the “Vienna” steamed along at a steady pace

in the North Sea hoping to lure German submarines to the surface, with

the aim of destroying them before they destroyed her. This was not for

the faint-hearted. The time in the North Sea proved fruitless so she was

sent to operate off the Cornish Coast in the area to which the German

submarines had moved but, again, had no success.

Herbert and Steele moved to another armed decoy ship, the “Baralong”,

and by May, 1915 they were back to their decoy duties. On 7 May the “Lusitania”

was lost along with nearly 1200 lives and many small steamers were also

being sunk. The “Baralong” had, in fact, picked up a distress

signal from the “Lusitania” but arrived too late to be of

help.

The “Baralong” now spent its time cruising in the area between

the south-west of England and the south of Ireland and, at last, on 19th

August, she encountered the Germans when she went to the aid of the S.S.

“Arabic”, a large liner, and the S.S. “Nicosian”.

Both had been attacked by a German submarine and the former had suffered

the loss of over 40 lives.

The “Baralong” arrived and indicated it was to rescue the

“Nicosian’s” crew but the submarine, rather than withdraw,

chose to continue to attack the “Nicosian”. In response, Herbert

decided to attack the submarine and, so, raised the White Ensign. Steele,

as gunnery officer, showed outstanding skill and courage in shattering

the submarine’s conning tower and, at risk to his own life, removing

one of the shells which had misfired in the port 12- pounder gun.

The submarine was incapacitated and the German crew escaped to the “Nicosian”

and the “Baralong’s” marines pursued them on board and,

no doubt with the “Lusitania” fresh in mind, killed the German

submarine captain and others of his crew.

In recognition of their actions the “Baralong’s” crew

were awarded £1000 and several decorations were bestowed on them.

Gordon Steele’s outstanding contribution was rewarded with the rare

honour of being transferred from the Royal Naval Reserve to the Royal

Navy. Before the end of the year he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant.

Actions such as those in which Steele took part convinced the Admiralty

of the great worth of the “Q- ships” and they played an increasing

role in the War.

After the “Baralong”, Steele served at Jutland on the battleship

“Royal Oak”.

In the autumn of 1917 he was given command of H.M.S. P63, a patrol boat

specially built for anti-submarine warfare and, later, he commanded H.M.S.

“Cornflower”.

The Great War ended on 11 November 1918 but Gordon Steele, now a regular,

continued to serve in the Royal Navy and was to be in action again within

a year.

Russia had been a member of the Allied coalition in the War until a series

of mutinies by its soldiers and sailors culminated in the October 1917

Revolution. The Russians withdrew from the War leaving the Germans free

to concentrate on the Western Front. In November 1917 the Russians began

negotiating with the Germans and, in March 1918, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

was signed which marked the formal end of Russian/German hostilities.

The Treaty also gave Germany the right to occupy substantial areas of

European Russia in which the Allies had large supplies of military equipment.

In March 1918 Allied forces had been sent to retrieve the supplies and,

also, to train the opposition Tsarist White Russian Army and, thereby,

came into conflict with the Russian revolutionaries. The conflict continued

into 1919 when the Allied forces guarding the military equipment were

trapped by the Russian winter and the British now raised the North Russia

Relief Force to secure their evacuation and the Force arrived in Russia

in June 1919.

On 17th June Lieutenant Augustine Agar won the Victoria Cross for an attack

in a Coastal Motor Boat (C.M.B.) at Kronstadt when a Russian cruiser was

sunk.

Against this background, Steele and Agar were to participate in a raid

on the Russian Navy moored in Kronstadt Harbour on the night of 18th August

1919. For their part in the action Steele won the Victoria Cross, Agar

the Distinguished Service Order and Commander Claude Dobson, who commanded

the attacking flotilla, the Victoria Cross.

The variety of Steele’s naval service to date had been wide and

he had already demonstrated his bravery, cool-headedness under fire, gunnery

skills and quick judgement. All of these qualities, and more, were to

be put to the test at Kronstadt Harbour.

C.M.B.s were introduced in April 1916, constructed of wood, 45 feet long,

very fast and lightweight, built to skip over the water and German minefields

and deliver torpedoes and, then, move away quickly. The boats weighed

4¼ tons and were later improved to travel at 40 knots and able

to use two torpedoes, mounted above the water line either side of the

hull. They were powered by twin petrol engines of 750 combined horse-power

and light, rapidfiring guns defended the boats. The C.M.B.s had been used

for the famous attack on Zeebrugge and Ostend on St. George’s Day

in 1918.

The crew on Steele’s C.M.B.was minimal with two lieutenants, a sublieutenant

together with two motor mechanics and a wireless operator.

Rear-Admiral Sir Walter Cowan, based at Björkö in the Gulf of

Finland, commanded the British naval force against the Bolsheviks and

his objective was to blockade the Bolshevik Northern Fleet. Agar’s

success emboldened Cowan to undertake the more ambitious attack on Kronstadt

Harbour which was a major Russian naval port which also protected Leningrad.

The attackers would have to overcome a series of defensive forts and a

destroyer which protected the approach to the Harbour. If they survived

these they would then face the Russian harbour gun defences and those

aboard the numerous ships in the Harbour.

The raid was undertaken by a flotilla of 7 C.M.B.s commanded by a very

experienced submarine captain, Commander C.C. Dobson D.S.O., R.N., who

was on board C.M.B. 31 commanded by Lieutenant R.H. Macbean, R.N..

Another boat was captained by Agar. Steele was second–in-command

and gunnery officer of C.M.B. No. 88D commanded by Lieutenant A. Dayrell-

Reed, D.S.O., R.N.. Dayrell-Reid had served in submarines and taken part,

as a navigator, in the Zeebrugge raid.

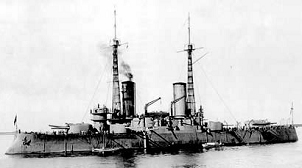

Aerial reconnaissance ahead of the attack showed that, moored immediately

to the left inside the Harbour, was the 23,300 ton battle-cruiser “Petropavlovsk”.

To its left, amongst other ships, was the 17,200 ton battleship “Andrei

Pervozvanni”. Each was armed with 12 inch and many other guns. Across

from the Harbour entrance the submarine depot ship “Pamiat-Azov”

was moored and, to the starboard of the Harbour entrance, 5 vessels were

moored alongside each other including the 15,170 ton cruiser “Rubric”.

The night of 17th/18th August 1919 was chosen for the attack and the flotilla

of 7 C.M.B.s started off at 10p.m.. Dayrell-Reed’s boat continued

to take on water which had to be pumped out at regular intervals but he

proceeded and his boat was one of three which were ahead of the others.

After hugging the Finnish coast they altered course for Kronstadt at 11.45p.m..

His was now one of only four which were up to speed and, after about half

an hour, they could see Kronstadt Island and, after a few miles, they

could see the series of small forts guarding Petrograd Bay.

By 1.00a.m. 3 boats, including Dayrell-Reed’s, were amongst the

forts.

Amazingly, neither the forts nor the Russian destroyer opened fire and,

as the three leading boats approached the Harbour, they formed up into

single file with Dayrell-Reid’s boat going in third. A few minutes

earlier a diversionary air attack had begun to provide cover for the C.M.B.s.

Once in the Harbour C.M.B. 79 fired at the “Pamiat Azov” and

hit it. The other two C.M.B.s opened fire but, as the Russians were still

quiet, Steele held fire. Now the Russians opened fire and Dayrell-Reed,

who was steering the C.M.B., was hit and his boat veered off course.

It was now that Gordon Steele took the initiative and, moving Dayrell-Reid

from the conning tower, could see he had been shot in the head. Steele

took control of the boat and continued and he and Dobson torpedoed the

battleship “Andrei Pervozvanni”. Steele then executed a very

tight turn, still under enemy fire, and, again, from only about 100 yards

gave the order to fire the other torpedo at the battle-cruiser “Petropavlovsk”

and, once more, hit the target. Before he heard the second torpedo hit,

Steele had to perform a turn within the minimum of space in order to allow

his boat to escape from the Harbour and this he did and then performed

another expertly executed tight turn to escape the Harbour entrance, still

under heavy Russian gun fire from within the Harbour.

Steele now proceeded back to Björkö and, on the journey, they

tended to Lieutenant Dayrell-Reed but he died later back at the base.

The commander of the flotilla, Commander Claude Dobson, was also awarded

the Victoria Cross and his and Lieutenant Steele’s citations were

published in the Supplement to the London Gazette of 11th November 1919

and Gordon Steele’s is reproduced in full above.

The attack had called for the highest bravery, undertaken in the dark

in a very confined space in a heavily defended harbour packed with well-armed

ships.

Additionally, the Coastal Motor Boats had to be manoeuvred with the highest

standards of skill at the same time as having to evade, as far as it was

in their power, heavy enemy gunfire and, at the same time, focus on firing

their torpedoes to destroy their targets. As second-in-command, Gordon

Steele had this responsibility thrust upon him in the direst of circumstances

and, in a life or death situation, carried out his duty to the highest

standards.

Gordon Steele continued serving in the Royal Navy. In 1929 he returned

to his old ship, the Training Ship “Worcester”, taking over

its command. He remained in charge, apart from anti-submarine duties in

the Second World War, until he retired in 1957.

Commander Steele had been the subject of an episode of “This is

Your Life” in 1958 but, on contacting the B.B.C., they informed

me that a copy of the broadcast had not been kept.

Gordon Steele was a Fellow of the Institute of Navigation, a Freeman of

the City of London and a Younger Brother of Trinity House.

Gordon Steele died on 4th January 1981 and lies buried in All Saints New

Cemetery, Winkleigh in Devon. |

|